eBPF Basics: A Guide to the Next Evolution in Systems Programming

Imagine rewriting kernel behavior on the fly. That’s the power of eBPF.

You’ve probably heard whispers about eBPF, maybe seen it pop up in a tech article, or heard someone in the know talk about it with a sense of awe. But what exactly is eBPF? Is it just another buzzword, or is it something more? Don’t worry—whether you’re curious but unsure, or have no idea what eBPF even stands for, this post is here to demystify it for you. It has taken me dozens of articles to understand what exactly is going on and I am still learning.

Let’s start with a bit of context. Operating system kernels are the beating heart of our modern computing systems, offering incredible functionality. But there’s a catch—if you want to add new features or tweak the kernel to meet specific needs, you’re often looking at years of development, debugging, and rigorous testing. Sounds daunting, right?

Enter eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter), a game-changer that’s transformed how we interact with operating systems. Think of it as a superpower for engineers: an in-kernel virtual machine that allows you to safely and efficiently extend kernel behavior—without the wait times or the risk of breaking the system. It’s fast, flexible, and robust, which is why leading tech companies have embraced it to redefine observability, networking, and security. With eBPF, they’re not just meeting performance and efficiency goals—they’re taking them to the next level.

eBPF represents a significant leap in operating system design, fundamentally shifting how developers interact with kernel-level functionality. Traditional kernel programming often required extensive knowledge of kernel internals, involved writing custom modules, and carried significant risks of destabilizing the system. eBPF eliminates many of these risks, allowing for dynamic, safe, and highly performant modifications to kernel behavior.

Unlike traditional approaches, eBPF operates within a well-defined virtual machine, supported by a robust verifier that ensures safety by analyzing bytecode before execution. This enables it to run highly optimized programs in sensitive contexts, such as networking and security, without compromising stability. Moreover, the scalability and adaptability of eBPF have made it a go-to technology in modern data centers, where companies leverage it for everything from load balancing to threat detection.

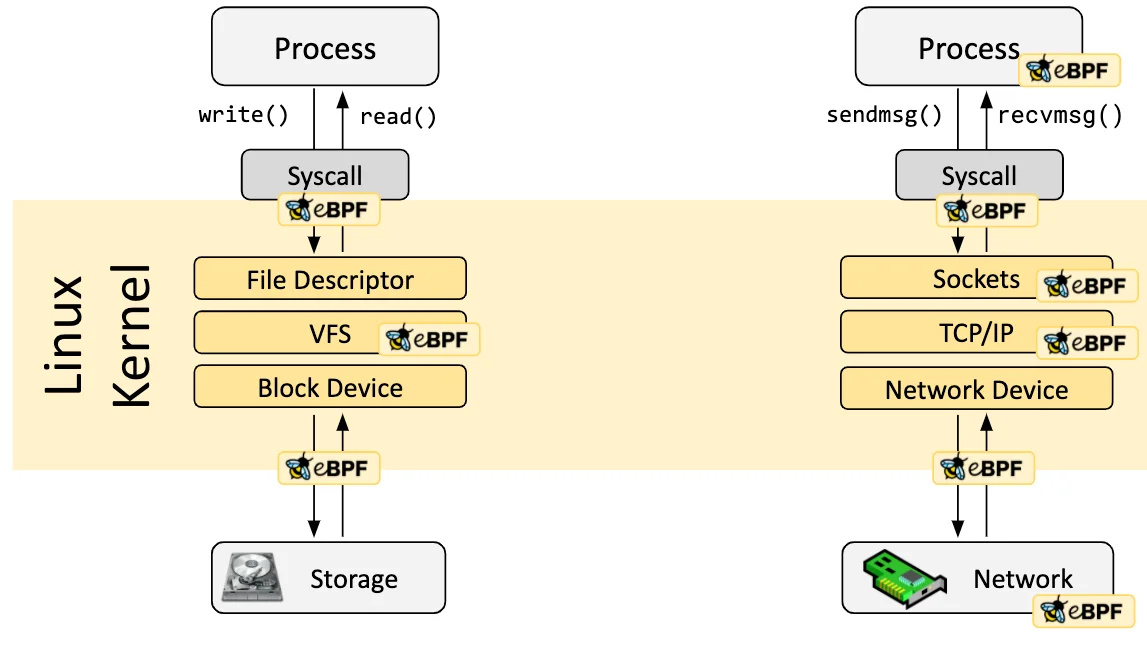

This technology offers unparalleled insights into major kernel functions, providing visibility into various networking stack layers, system calls, function entry and exit points, and kernel tracepoints. These capabilities have driven the adoption of eBPF across diverse domains, such as observability, networking, and security. Leading technology companies, including Meta, Google, Microsoft

How do I write eBPF programs and their architecture

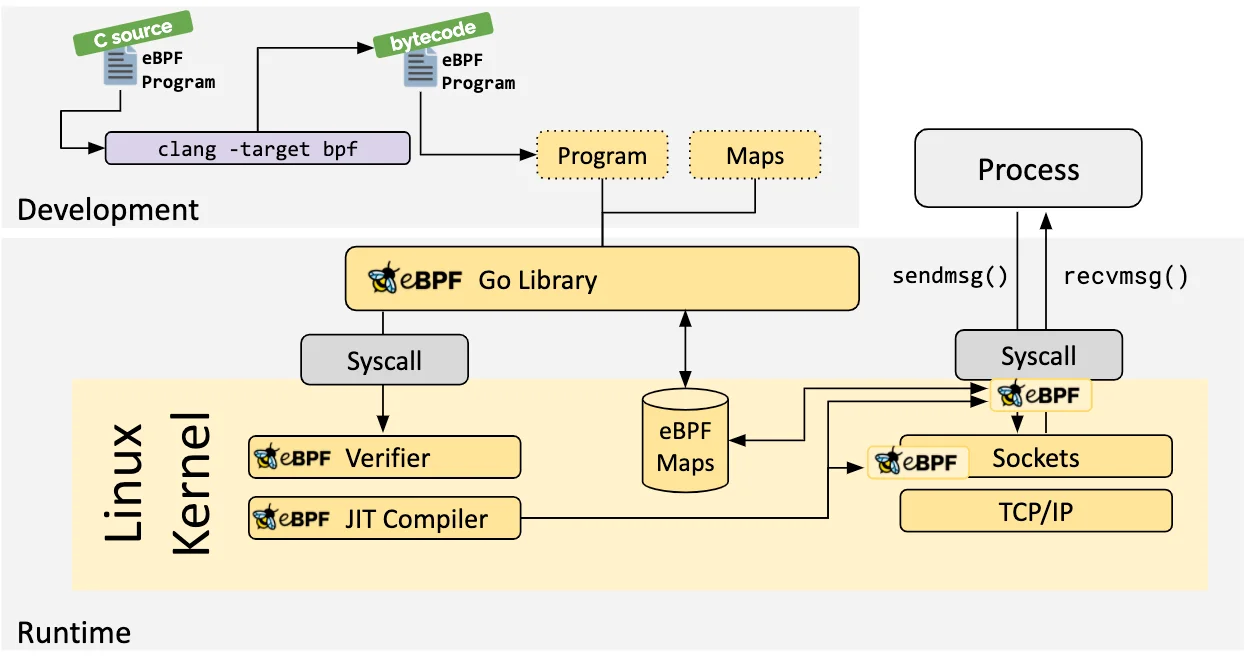

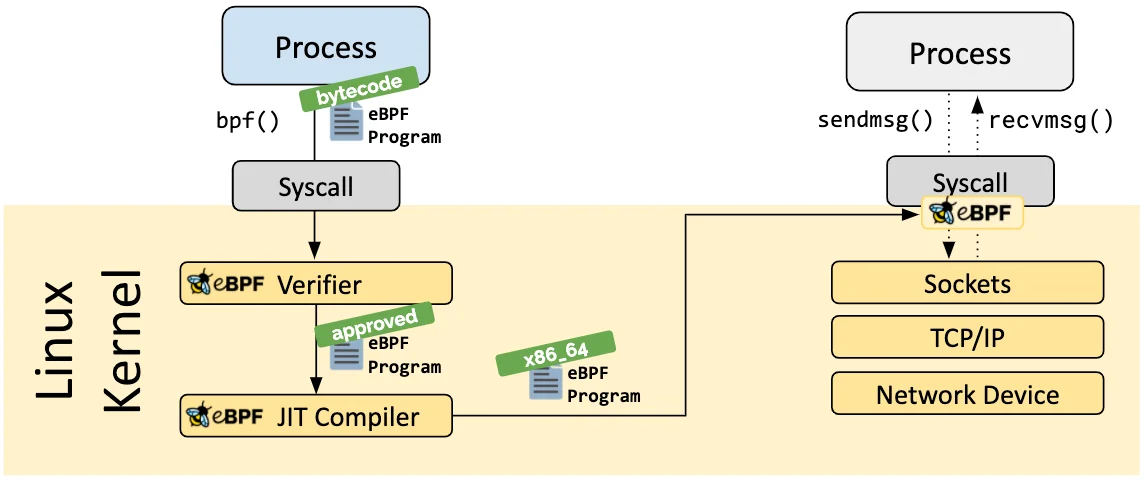

Engineers can write eBPF programs in C/C++, Rust, Go, or eBPF bytecode directly (it’s rarely done in practice). When the program is ready to be loaded into the kernel for execution, it’s first validated by the eBPF verifier that makes sure the program is safe to add to the kernel and won’t crash it. More details on how the verifier works can be found in the next section. If the verifier confirmed the program is safe to run, it then gets JIT-compiled into machine code that is attached to target events (hooks)

Hooks. eBPF programs are event-driven and as such can be inserted to execute at different “hooks” in the normal kernel execution. eBPF program hooks are largely defined by the program type. The program type determines where and how the eBPF program can be attached in the kernel and what context the program will operate on. Each program type corresponds to specific kernel subsystems or events and dictates the program’s interaction with the system. Table 1 highlights some of the main program types and their use cases. For more comprehensive documentation on them, refer to

| Program type | Hook location | Primary use case |

|---|---|---|

SOCKET_FILTER | Sockets | Packet filtering and monitoring. |

XDP | Network Interface Driver | High-performance packet processing. |

SCHED_CLS | Traffic Control | Traffic shaping and quality of service (QoS). |

KPROBE | Kernel Function Entry/Exit | Tracing and debugging kernel functions. |

TRACEPOINT | Kernel Tracepoints | Monitoring system events like syscalls. |

CGROUP_SKB | Control Groups | Monitoring and controlling packets in cGroups. |

LWT_IN | Lightweight Tunnel Ingress | Handling packets entering tunnels. |

NETFILTER | Netfilter Hooks | Custom packet filtering. |

PERF_EVENT | Performance Events | Monitoring hardware performance counters. |

RAW_TRACEPOINT | Low-level Tracepoints | Advanced kernel tracing with low overhead. |

LSM | Linux Security Module | Enforcing custom security policies. |

STRUCT_OPS | Kernel Structures | Overriding kernel structure operations. |

Programming eBPF. Oftentimes, eBPF programs are written indirectly, using higher-level infrastructures such as Cilium, bcc, bpftrace, Tetragon, and others

Loading and verifying. After eBPF program has been developed, it can be loaded into the kernel to be attached at the predefined hook using bpf system call. Users typically do not need to do it manually, since existing libraries take care of that. Before being attached to the defined hook, eBPF applications go through verification and JIT compilation. JIT compilation translates eBPF bytecode into machine-specific instruction set to optimize execution speed and makes programs run as if natively compiled kernel code

Helper calls. Helper functions allow eBPF programs to directly and safely interact with the kernel. There is a predefined constantly-growing set of them to avoid calling arbitrary unsafe kernel functions. Having such a set is also important for cross-compatibility of eBPF code between kernel version. As they are defined as part of the userspace API, programmers can rely on them not disappearing or changing. Helpers can generate random numbers, get current date and time, help access eBPF maps (more about maps in a later section), create loops, and print logs, etc

Tail and function calls. Taiд calls allow to break upeBPF program into multiple parts and call one after the other. They are different from function calls in that control does not go back to the previous subprogram, but keeps going forward sequentially. To use tail calls, one needs to add BPF_MAP_TYPE_PROG_ARRAY map to their program and fill with reference to other programs and then use bpf_tail_call with a reference to the map and array index to perform the tail call

eBPF Verifier

Using eBPF is generally safer than loading custom modules into the kernel, since all eBPF programs must pass the verification step to be executed. It is crucial that eBPF programs do not affect the stability and correctness of the operating system and do not compromise it in any way. The verifier validates that the program meets several conditions, such as: (1) the process loading the eBPF program holds the required privileges to execute it in the kernel; (2) the loaded program does not crash or otherwise harm the system; (3) it always runs to completion; (4) it does not access memory that it does not validate

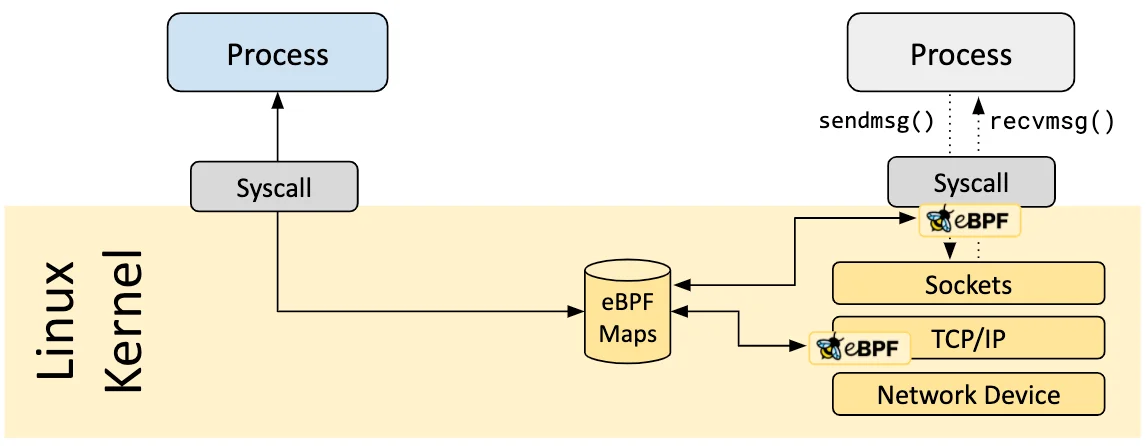

eBPF Maps

eBPF maps provide a way to store and share different data between kernel and user space. As eBPF programs are stateless by default, they add the ability to hold information for the program’s runtime duration. Some maps exist to support specific helper functions. Maps themselves are also accessed via helper functions from in-kernel eBPF programs and via bpf syscall from the user space

Broadly, eBPF maps can be categorized into four main groups. The fundamental maps include arrays and hash tables (BPF_MAP_TYPE_ARRAY, BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH) with their per-CPU and LRU variants. Advanced data structures comprise Bloom filters (BPF_MAP_TYPE_BLOOM_FILTER) and LPM tries (BPF_MAP_TYPE_LPM_TRIE). System resource maps handle cgroup storage and device mapping (BPF_MAP_TYPE_CGROUP_STORAGE, BPF_MAP_TYPE_DEVMAP), while networking is supported through various socket-specific maps (BPF_MAP_TYPE_SOCKMAP, BPF_MAP_TYPE_XSKMAP)

Interestingly, eBPF maps, despite being widely used, have barely been studied. A recent study benchmarked their performance characteristics and demostrated access overhead of different maps

eBPF has fundamentally changed how we interact with operating systems. By enabling safe, dynamic, and efficient modifications to kernel behavior, it solves problems that once required years of development and significant risk. This technology is already widely adopted in networking, observability, and security, proving its real-world value across industries.

Its tools and libraries make it increasingly accessible, and its potential is still growing as more use cases emerge. For engineers, eBPF is not just a tool—it’s an opportunity to innovate directly at the heart of the system.

If you’re curious, start small. Explore the libraries, try writing a basic program, and see the impact for yourself. The future of system-level development is here, and eBPF is leading the way.

I will definitely be writing much more about it as I have read dozens of research papers on it, so stay tuned!