Wait, Wi-Fi Doesn’t Work Underwater?! Underwater Wireless Communications

Turns out, Wi-Fi isn’t a fan of water! So how do submarines, underwater drones, and ocean explorers stay connected?

My boyfriend is big on swimming. Once, he mentioned he’d like to get underwater headphones to listen to music while swimming. It never really occurred to me you need special headphones for that—I avoid swimming pools and water at any cost—but it does make sense.

When I researched headphones for him, I realized that none of them were quite what I was looking for (disappointed face). It feels like underwater headphone companies have dug up 20-year-old tech and are still selling us “download-your-music-on-an-SD-card-and-listen-in-the-pool” models.

But then again, because swimmers are both in the air and underwater, it apparently makes things harder and then might not work? Are any of them even worth buying? There are multiple dozens of Reddit posts on the topic and even comparison articles from major news outlets.

As I dove into Reddit threads and news comparisons, I realized that the problem isn’t just headphones. Wireless communication underwater is its own complex, fascinating challenge. Today, I am not trying to sell you underwater headphones (not that I would not want to). Instead, I want to dive deeper into what makes wireless communication so hard underwater and how it’s tackled across different fields.

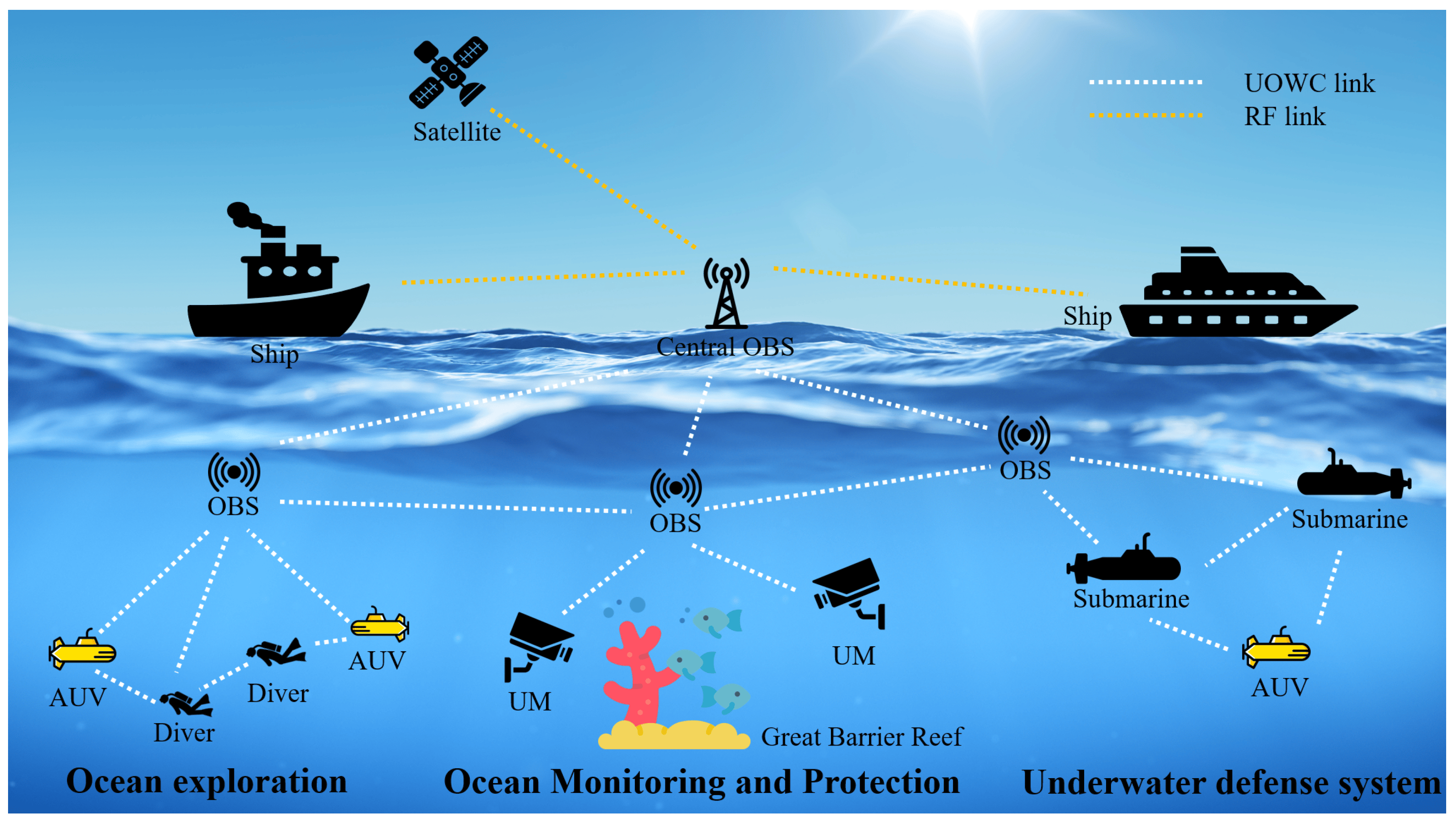

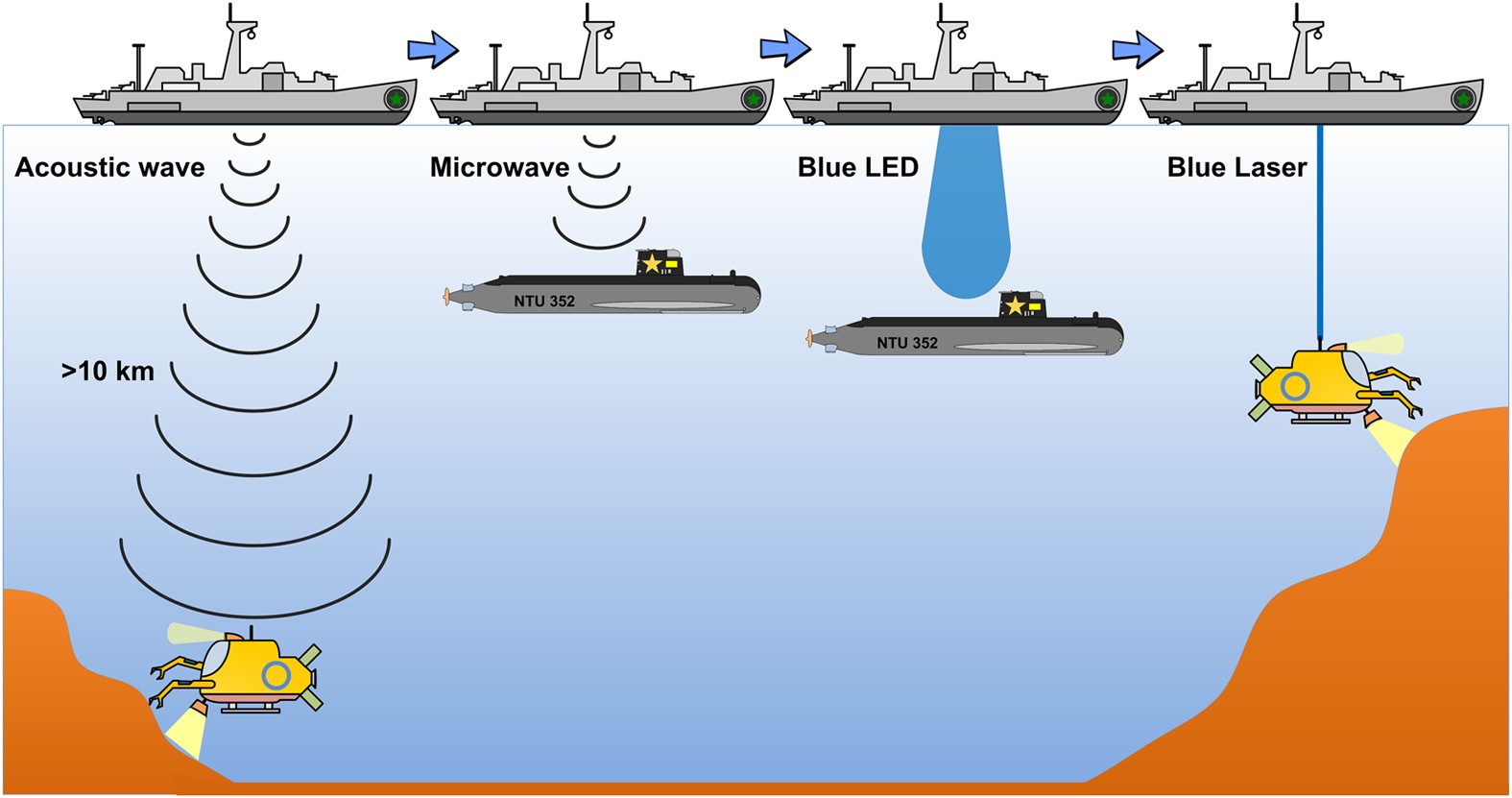

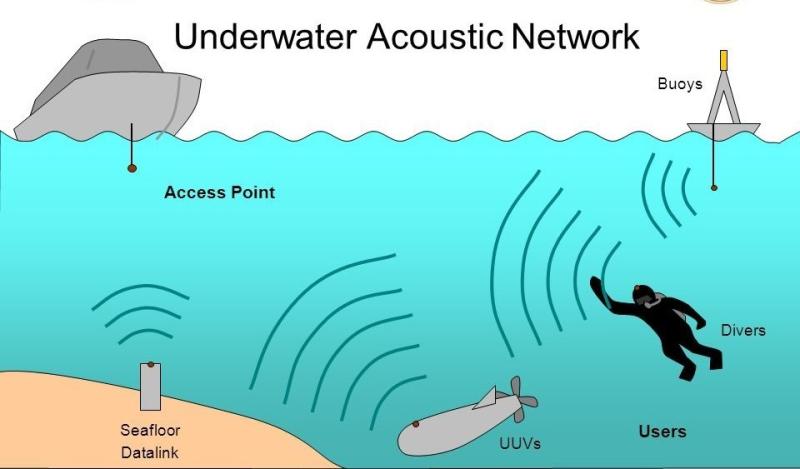

Underwater wireless communications (UWC) are vastly important for ocean explorations, military and security applications, environmental monitoring, and offshore industries. Marine biologists and climate researchers install devices to keep track of ocean pollution, for real-time coral reef studies, and animal tagging to study migration patters. They are also vital for submarine communication, detecting oil spills, supporting undersea farms, and guiding divers during exploration missions. UWC make it possible to gather critical data and carry out operations in some of the most challenging environments on Earth.

As you can imagine, using wireless communications for such purposes is much more convenient than dealing with heavy and expensive cables. Such devices also have larger potential for reduced deployment and maintenance cost. Using UWC also offers a greater flexibility for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) and Remote Operated Vehicles (ROVs), which could enable real-time communication for mobile devices.

Radio Frequency Communications

In usual terrestial communications, we primarily use radio waves (or radio frequency - RF), which are just electromagnetic waves that transmit data wirelessly. Different applications (e.g., Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, cellular) use specific frequency bands to not interfere with other signals. RF communications on air are incredibly versatile and have come a long way. However, they barely propagate in the water.

Underwater, the propagation of RF signals is drastically affected by the environment, primarily water salinity. This is because saltwater is a good conductor of electricity, and electromagnetic waves lose energy quickly as they induce currents in the water. This process is called attenuation.

For usual terrestrial communication frequencies, such as the very high and ultra-high frequency ranges (30–300 MHz, used by TV broadcasts and Wi-Fi), they can only propagate ~cm in seawater. For comparison, the same frequencies can travel many kilometers in the air.

Lower frequency signals, however, don’t suffer from the signal loss (attenuation) as much. At extremely and very-low frequency (ELF and VLF, respectively), signal attenuation is low enough to allow for reliable communications over several kilometers. However, these frequencies come with significant limitations, primarily on bandwidth. ELF bandwidth is only 3 Hz to 3 kHz and VLF - 3 kHz to 30 kHz. Those frequency ranges are not wide enough to enable transmissions at high data rates. For context, Wi-Fi operates in the gigahertz (GHz) range and can transmit data at speeds of hundreds of megabits per second (Mbps). ELF and VLF can only handle up to 3 kbps (kilobits per second), which is more suitable for sending simple commands or text data.

When we look at how exactly RF waves attenuate underwater, frequency is a key factor, especially since it’s a much larger number than others. Underwater RF communications signal attenuates like so:

\[\alpha(f) = \sqrt{\pi \sigma \mu_0} \sqrt{f},\]where \(\alpha(f)\) is channel attenuation per meter, \(f\) - RF (carrier) signal frequency in Hertz, \(\sigma\) - water conductivity in Siemens per meter, \(\mu_0 \approx 4\pi \cdot 10^{-7} \ {H/m}\) - vacuum permeability (water has the same permeability as vacuum). Now, conductivity is a function of salinity and temperature, for seawater, it is around 4.3 \({S/m}\), but for fresh water - only 0.001 to 0.01 \({S/m}\), which is two-three magnitudes lower and plays a huge role. Thus, the main aspect to be considered to characterize the wireless channel for RF transmission is the salinity of the water.

RF signals are also highly susceptible to the Doppler effect, a phenomenon where the frequency of a wave changes relative to the movement of the transmitter or receiver. This effect can cause significant signal distortion in environments with moving objects, such as underwater drones, submarines, or waves. The Doppler effect becomes particularly problematic for maintaining reliable communication, as it can interfere with data decoding and synchronization, especially at higher frequencies. These limitations mean that while RF signals hold promise in specific use cases, they often need to be combined with other technologies, like acoustic or optical systems, to provide robust underwater communication.

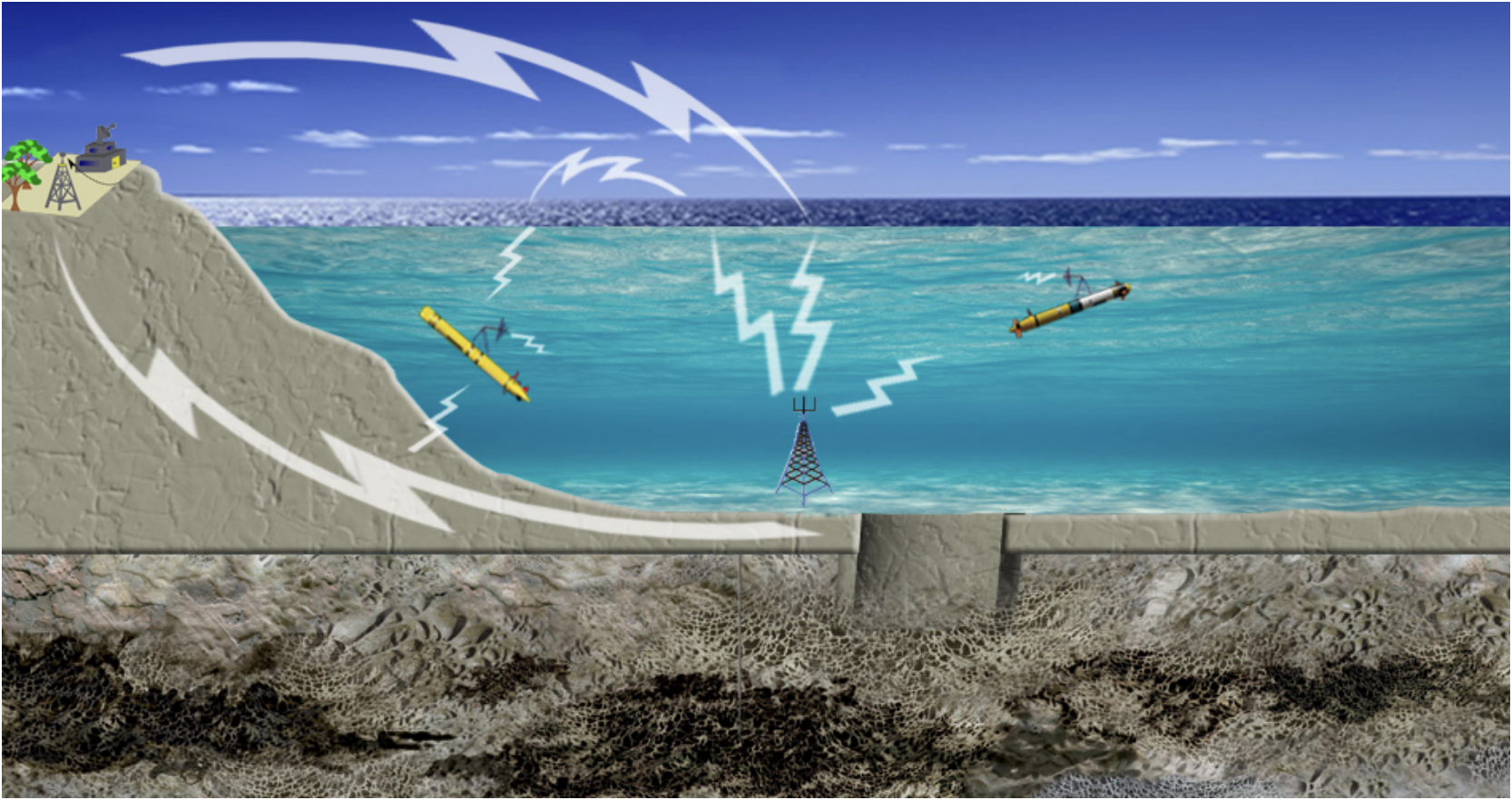

Despite being used in naval and environmental applications, underwater RF communications have large and expensive equipment and require high transmission power. Submarines often rely on RF in ELF or VLF for receiving orders from command centers, as these signals can penetrate deep into the ocean. However, they cannot transmit back using the same method because generating these signals requires massive infrastructure. Additionally, all the equipment must be properly encapsulated for operation in the underwater environment

One advantage of RF signals is that they can cross the water-air boundary, making them useful for communication between underwater devices and surface stations, such as buoys or drones. Additionally, RF signals can propagate through the seabed, making them promising for use in shallow water environments, since waves can then travel in multiple directions (multipath) and could be recombined together at the receiver.

Optical Communications

Driven by the need for higher bandwidths and data rates that RF simply couldn’t achieve, researchers have explored other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum for underwater communication-light waves in the optical frequency range (\(300 GHz − 10^{15} Hz\)). Unlike RF signals, which treat water as a conductor, light waves in the optical frequency range interact with water as a dielectric. This shift occurs because seawater transitions from behaving like a conductor to acting like a dielectric medium at around 250 GHz. This happens because at high-frequency oscillations, seawater ions cannot respond to fast enough to interact with the waves and less of the wave energy dissipates as heat.

Optical communications offer unique advantages but come with their own challenges. For one, light waves can propagate only over tens of meters in water due to absorption and scattering, which are more significant than in air. However, they benefit from a negligible Doppler spread due to the high speed of light in seawater. The refractive index of seawater, approximately \(n ∼ 1.33\) reduces the speed of light in the medium to around \(c_{light} = 2.25 \cdot 10^8 {m/s}\). Despite this reduction compared to the speed of light in a vacuum, the speed remains significantly higher than the velocities typically encountered in underwater scenarios, such as the movement of underwater vehicles or water currents. This high propagation speed minimizes the relative frequency shifts caused by motion, effectively rendering Doppler spread insignificant in the context of optical communication under water.

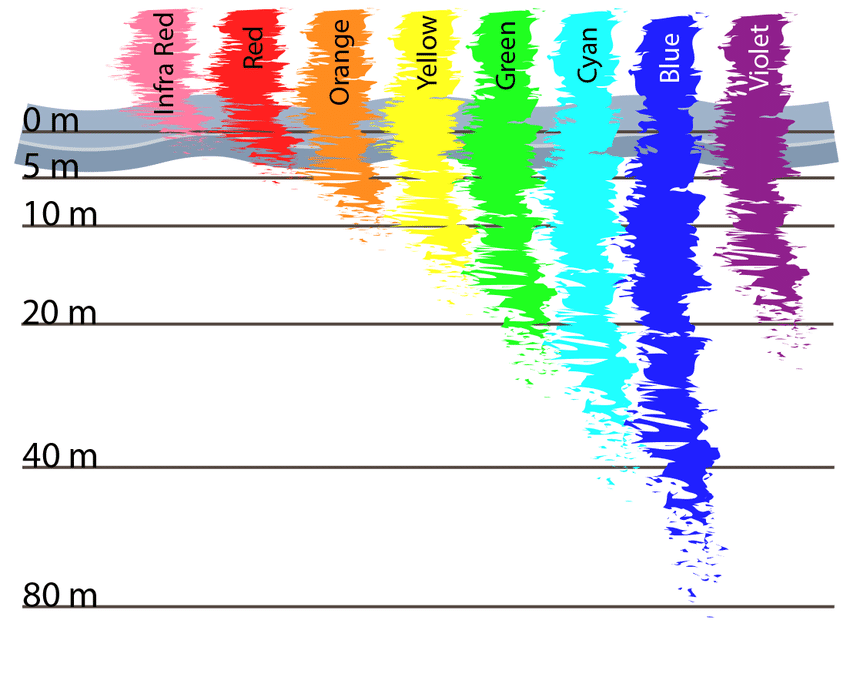

The effective transmission distance depends heavily on the frequency range of the optical signal. Signals within the blue-green optical window experience significantly lower propagation attenuation due to reduced absorption and scattering in this part of the spectrum, making it ideal for underwater communication.

However, optical communication generally requires a clear line-of-sight between the transmitter and receiver. This necessity introduces challenges in maintaining the communication link, often requiring some form of direction tracking or alignment mechanism to ensure continuous connectivity as the transmitter or receiver moves or environmental conditions change.

The propagation of light underwater is influenced by two main categories: inherent optical properties (IOPs) and apparent optical properties (AOPs). IOPs pertain to the characteristics of the medium itself (water), while AOPs are linked to the light source, such as its directionality and intensity. Among these, IOPs play a more critical role in determining how light propagates through water, particularly through absorption and scattering processes.

Absorption occurs at various components present in the water, including chlorophyll in phytoplankton, colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM), water molecules, and dissolved salts. These elements absorb light at specific wavelengths, significantly impacting the signal’s strength over distance.

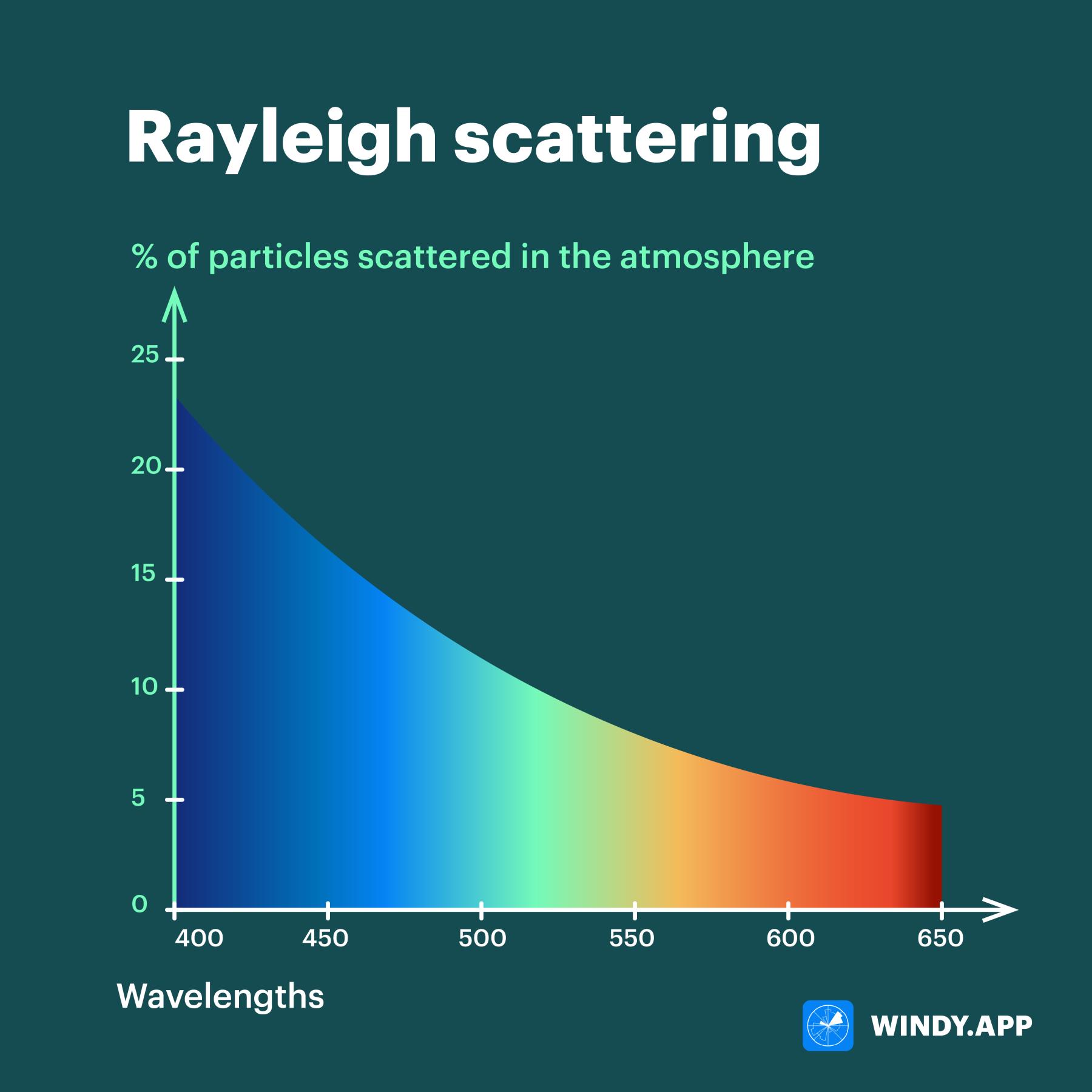

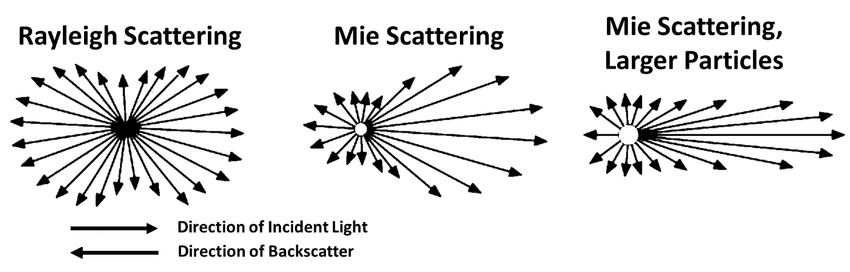

Scattering, on the other hand, changes the direction of photons as they interact with the medium. Scattering is caused by salt ions in pure water, particulate matter, and even interference from fish and other aquatic organisms. The nature of scattering depends on the size of the scattering particles relative to the wavelength of light. For particles smaller than the wavelength, scattering is described by the Rayleigh model, while for particles larger than the wavelength, it is governed by Mie theory. This scattering not only affects signal strength but also disrupts the coherence of the light beam, further limiting the effective range and reliability of underwater optical communication.

In addition to absorption and scattering, many applications utilize the backscattering coefficient that measures the amount of light scattered back toward the transmitter. The backscattering coefficient is particularly valuable for assessing water quality, as it provides insights into water turbidity. This information can be leveraged to design intelligent optical communication systems, such as smart transmitters that dynamically adjust transmission power and data rates based on the current water conditions.

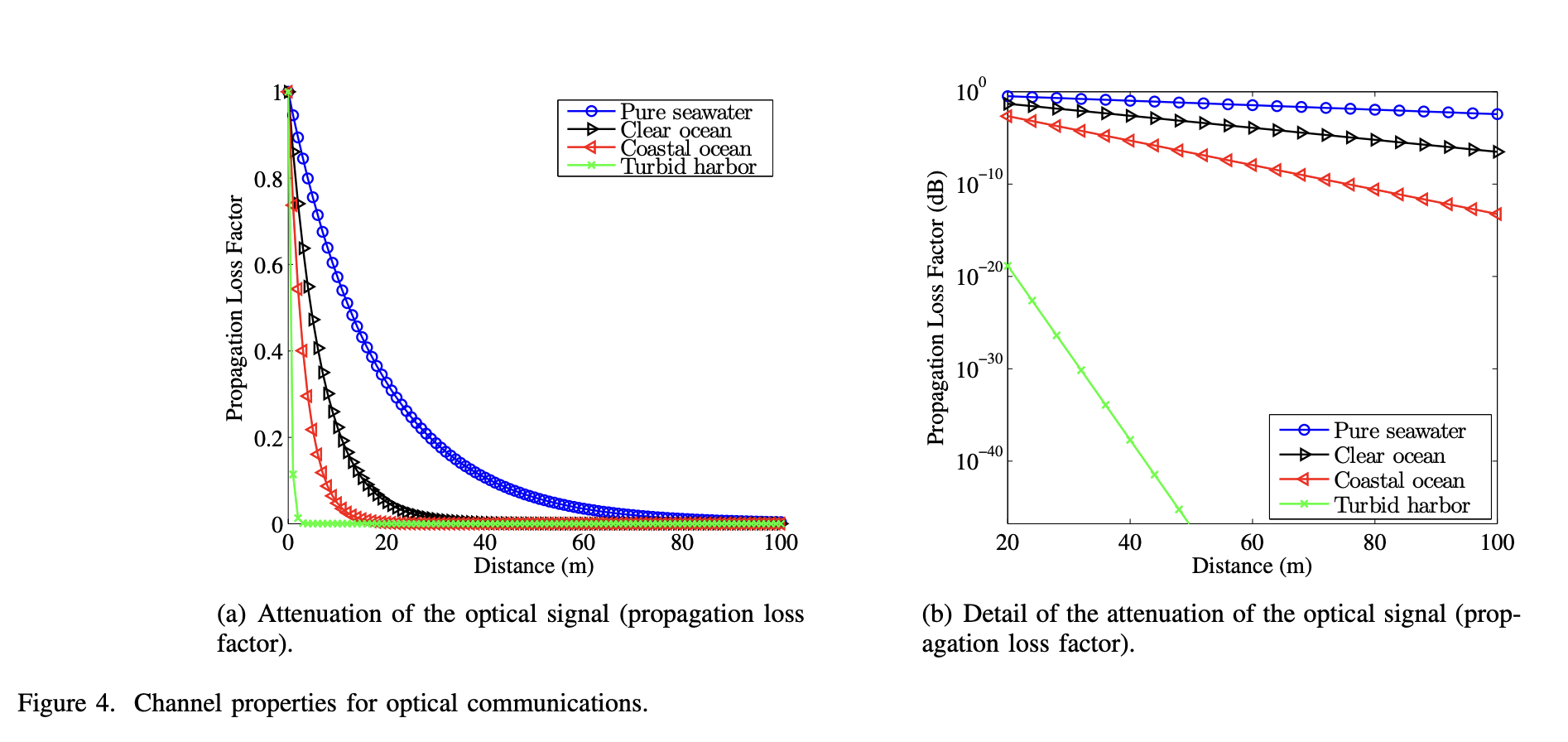

Water quality varies significantly across different locations worldwid due to differences in biological activity, sedimentation, and human impact. For example, the Pacific Ocean tends to have clearer waters in open regions due to lower sedimentation and biological particles, whereas coastal waters in regions like the Atlantic Ocean or Indian Ocean often exhibit higher turbidity due to denser populations, river outflows, and industrial activity. Furthermore, nutrient-rich upwelling zones, such as those off the coast of South America, lead to higher particle concentrations, impacting both scattering and absorption characteristics. Furthermore, researchers specify water clarity levels since optical signals are easily influenced by any changes in the environment. In pure seawater, most signal loss arises from absorption, with minimal scattering effects. In clear ocean water, scattering losses increase due to a higher concentration of particles, while coastal ocean water features even greater particle concentrations, further amplifying both scattering and absorption losses. At the extreme, turbid harbor and estuary waters exhibit the highest particle concentrations, resulting in substantial degradation of optical signals. Understanding these variations is essential for optimizing underwater communication systems for specific environments.

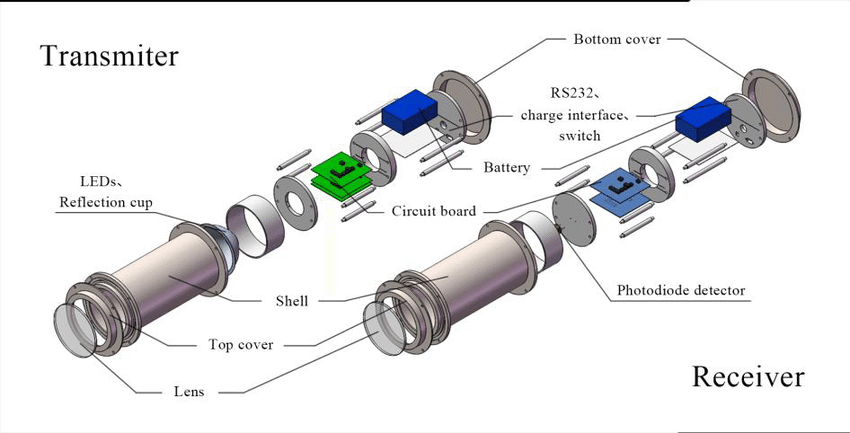

Underwater optical communication systems rely on specialized components at both the transmitter and receiver ends, tailored to meet specific requirements. At the transmitter end, generating optical signals from electrical inputs involves three key components: an optical source, a projection optical system, and a beam steering mechanism. The optical source can be either a laser or an LED, each with distinct characteristics suited to various system needs. Lasers are typically selected based on the application’s requirements.

Establishing a spatially aligned point-to-point connection between the transmitter and receiver is critical to ensure sufficient signal power for decoding. Any misalignment can significantly degrade performance. Emerging research focuses on smart optical systems, where transmitters dynamically estimate water quality via backscattered signals and adjust transmission power accordingly, optimizing performance in varying underwater conditions.

The receiver end consists of collection optics, such as a single lens or an array of lenses, paired with a photodetector to convert optical signals into electrical ones. The choice of photosensor depends on the application.

While the ideal photosensor would be cheap, small, robust, and power-efficient, current technology cannot meet all these criteria simultaneously, necessitating compromises. These components collectively define the performance and feasibility of underwater optical communication systems, emphasizing the importance of careful selection and alignment for reliable operation.

Underwater optical communication faces a variety of challenges that stem from both the physical environment and the limitations of current technologies. It has a surprising amount of noise sources: excess noise (from signal amplification), quantum shot noise (caused by random variations in photon counts), optical excess noise (arising from transmitter imperfections), optical background noise due to environmental clutter, photodetector dark current noise—caused by electrical current leakage, and electronic noise from components!

To address these issues, optical systems must also navigate several operational challenges. The channel model is heavily influenced by water type, turbidity, and the size of the receiver lens aperture. Channel dispersion must be quantified to configure the most effective signal detection methods, while changes in directionality necessitate special signal processing algorithms. Transmitters and receivers must often rely on closed-loop feedback mechanisms and filter received signals to counteract environmental noise, applying time-domain, frequency-domain, or spatial filtering as needed. The dependence on water turbidity remains a major constraint, limiting propagation distance and data rates. Emerging technologies, such as smart transmitters capable of processing backscattered signals, hold promise for dynamically adapting power and data rates to varying environmental conditions.

Despite these hurdles, underwater optical communication has found applications in several key areas, including underwater wireless sensor networks, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), and real-time data transfer for oceanographic research. These systems are crucial for monitoring marine environments, exploring the deep sea, and enabling military and commercial operations underwater. However, significant challenges remain, such as expanding the propagation range, achieving higher data rates, and developing robust, cost-effective components that can operate reliably in diverse aquatic environments. Overcoming these obstacles will be critical for advancing underwater optical communication and unlocking its full potential in the years to come.

Acoustic Communications

Acoustic communication is a key method for transmitting information underwater, particularly over long distances where optical communication is limited. Unlike optical signals, acoustic waves can propagate over kilometers with relatively low attenuation, depending on factors such as frequency and water conditions. The propagation speed of sound underwater is approximately \(1500 {m/s}\), significantly slower than the speed of light, which results in challenges such as high latency and multipath propagation.

Acoustic waves are generated using transducers, devices that convert electrical signals into sound waves. These waves then propagate through the water and are received by hydrophones, which detect the sound and convert it back into electrical signals for processing. This fundamental process underpins underwater acoustic communication systems, which play a crucial role in long-distance data transmission in marine environments.

One key application of this technology is communication with submarines. Submarines rely on acoustic signals to maintain secure and long-range communication while submerged, as sound waves can travel great distances underwater with relatively low attenuation. Similarly, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), which are robotic systems used for tasks such as underwater exploration, environmental monitoring, and industrial operations, use acoustic communication to receive commands and transmit data back to their operators.

Another important application involves sonobuoys, small, floating platforms equipped with hydrophones and communication systems. These devices are deployed in the ocean to monitor underwater activity. For instance, sonobuoys are used in anti-submarine warfare to detect and track submarines, in marine biology to monitor the movements of marine animals, and in oceanography to collect data on environmental conditions. Sonobuoys transmit the data they collect to surface vessels or aircraft via radio signals, making them a critical tool for monitoring underwater environments.

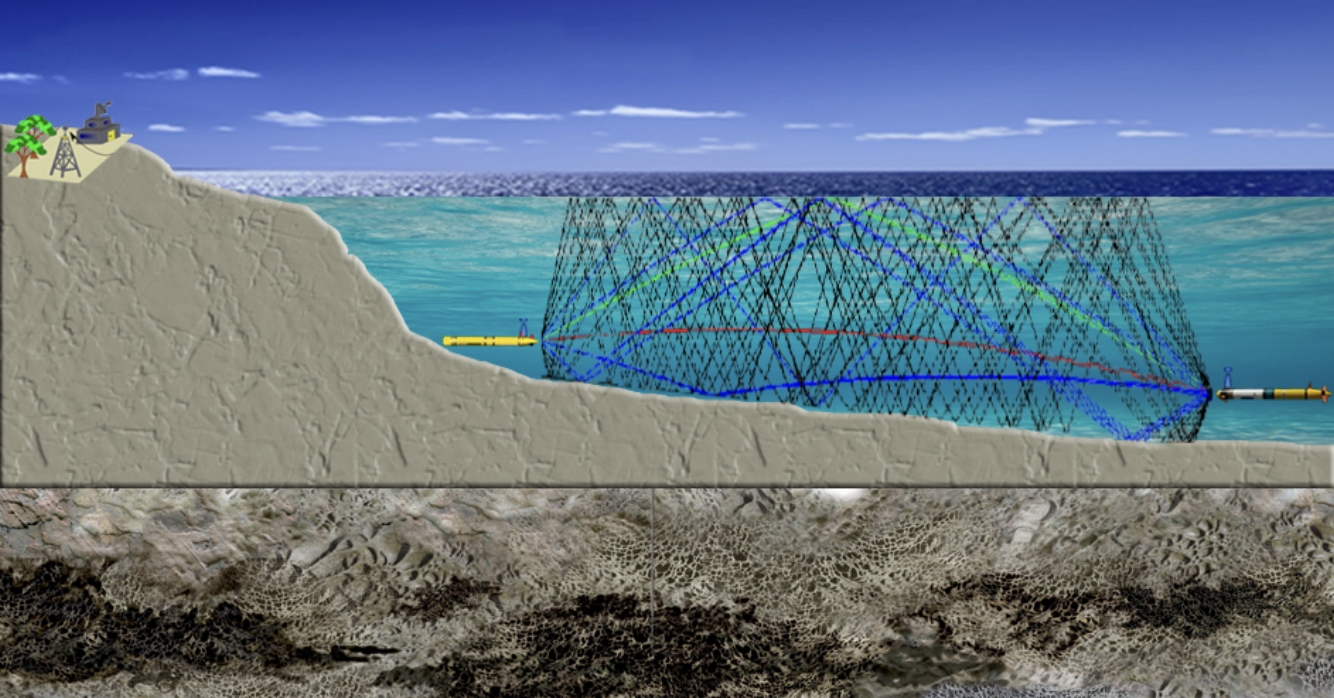

An essential natural phenomenon that enhances acoustic communication is the SOFAR channel (Sound Fixing and Ranging channel). This is a layer in the ocean where sound waves can travel extremely long distances with minimal energy loss. The SOFAR channel forms due to a combination of temperature, salinity, and pressure conditions, which create a “trap” for sound waves. This allows signals to propagate efficiently across vast oceanic distances, making it particularly useful for submarine communication, long-range monitoring, and even detecting underwater events such as earthquakes or underwater explosions.

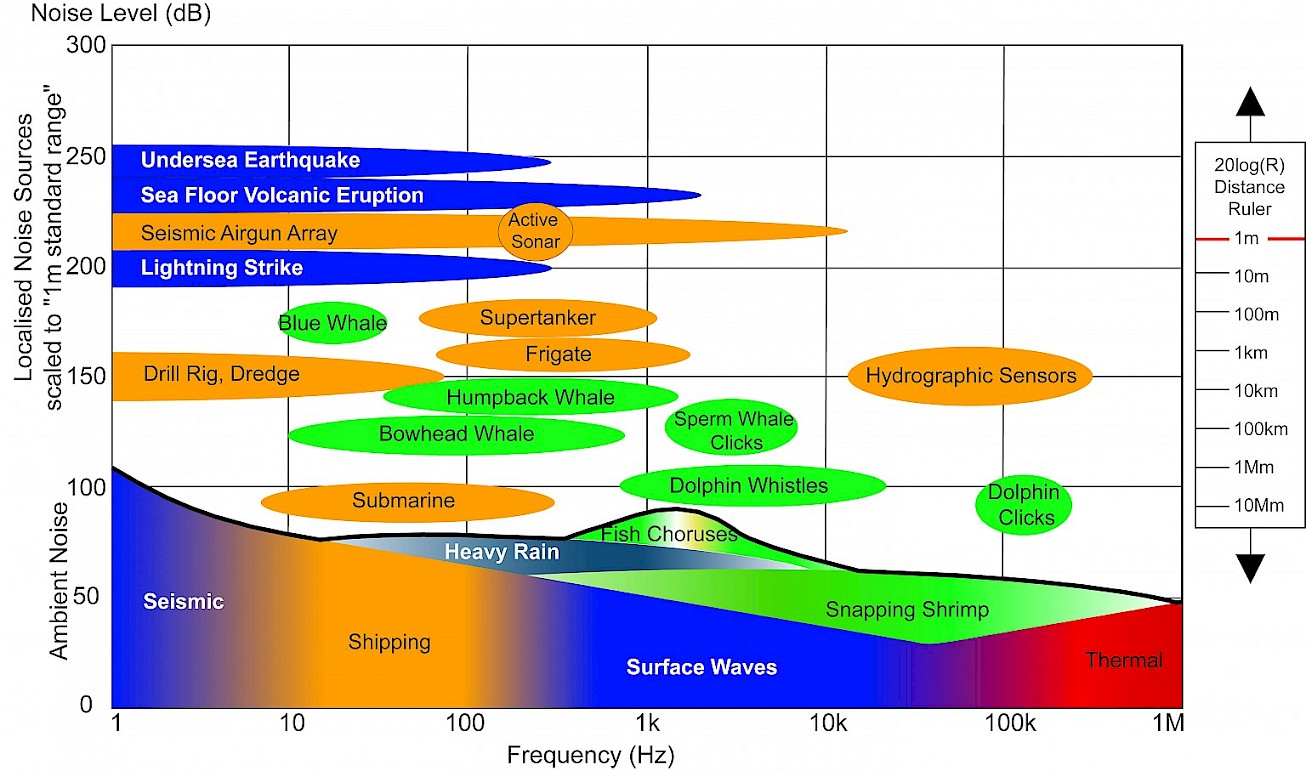

However, acoustic communication faces significant challenges. One of the primary limitations is bandwidth, which is restricted to the kilohertz range, resulting in low data rates (typically in the kilobits per second range). This makes acoustic communication unsuitable for high-speed data transfer. Moreover, attenuation increases with frequency, which means higher frequencies experience greater path loss, further limiting the effective bandwidth. Over long distances, such as 100 kilometers, the usable bandwidth can drop sharply to just 2 kHz.

Multipath propagation also poses a major challenge. As sound waves reflect off surfaces such as the seabed and the water surface, they create a multipath channel. These reflections cause signal interference, longer delays, and degraded data quality. Additionally, underwater environments are filled with non-Gaussian noise from both natural and human sources, including wind, marine life, shipping activities, and offshore wind farms. Modeling this noise and accounting for acoustic channel fading remains a complex task.

Additionally, human activities contribute to underwater noise, with shipping traffic and wind farms introducing disruptions that further degrade signal quality. Channel capacity, which determines the maximum amount of information that can be transmitted, depends heavily on transmission distance and environmental factors. Longer distances sharply reduce bandwidth, exacerbating the challenges of low data rates.

Another significant issue is the Doppler effect, which arises from relative motion between the transmitter, receiver, and moving water. Unlike in satellite communication, where the high speed of light makes the Doppler effect negligible, in acoustic communication, the relatively low speed of sound (~1500 m/s) makes the Doppler effect a significant factor. Frequency shifts and spreading caused by the Doppler effect lead to delays and synchronization issues, complicating signal processing. The Doppler effect is proportional to \(a = {v/c}\), where \(v\) is the relative velocity and \(c\) is the speed of sound. This proportionality makes even modest motion in underwater environments impactful, resulting in phase errors and delays that must be compensated for in communication systems.

Despite these challenges, acoustic communication remains the backbone of underwater data exchange due to its ability to cover long distances and navigate the unique properties of aquatic environments. Advances in transducer design, noise mitigation techniques, and sophisticated signal processing algorithms are critical to overcoming these limitations and enhancing the reliability and efficiency of acoustic communication systems. These innovations will ensure the continued viability of this technology in applications ranging from military operations to marine research and environmental monitoring.

Underwater wireless communication is an indispensable tool in modern marine exploration, research, and industry. Each mode—radio frequency, optical, and acoustic—has its unique strengths and challenges, making them suitable for specific applications. While RF struggles with range and attenuation, optical systems excel in high-speed, short-range data transfer, and acoustic communication remains the backbone for long-distance transmissions.

The limitations of these technologies are significant, but they are being actively addressed through advancements in hybrid systems, smarter signal processing, and adaptable hardware. These innovations will shape the future of underwater connectivity, enabling deeper exploration, improved environmental monitoring, and more efficient underwater operations.

As we tackle the challenges of range, speed, and reliability, these systems are pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in one of Earth’s most demanding environments. The future is bright—or, in the case of optical signals, blue-green.

So next time you’re frustrated by slow Wi-Fi, just remember: at least you’re not trying to stream Netflix from a submarine. 🌊